Nature Deficit Disorder: Cultural Autism

N.D.D.

What we are talking about is what Richard Louv, author of Last Child in the Woods, calls atrophy of the senses. Our children’s generation spends most of its time on secondary information – the media – rather than in direct, first person experience. Some think we may be losing the capacity to experience the environment directly, and as a result there is more tunnel vision about our own circumstances and increased feelings of loneliness.

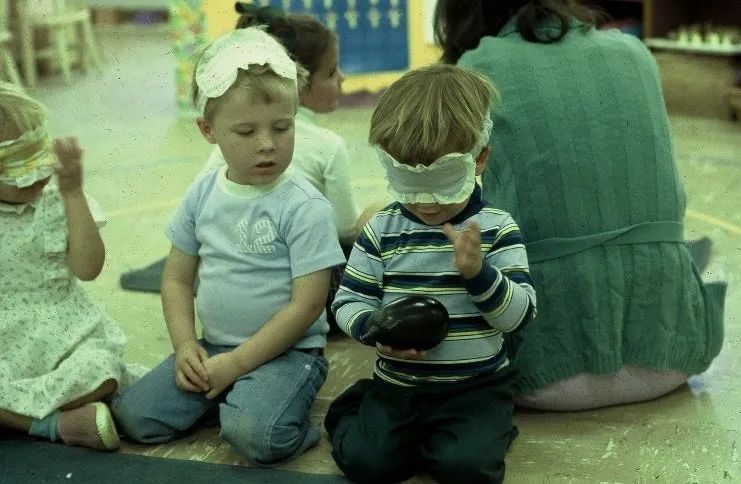

Children learn and build themselves through their senses. This is a basic premise of Montessori education, and sensory activity based on hands-on movement is at the core of how every subject is taught, from geometry to botany to music to geography.

This is all good news for children, but life, especially in the summer, is at home. So how can we help our children get more integrated with nature as the summer approaches?

About Play

In the years from 1997 to 2003 when Louv published his book, there was a 50% decrease in free outside play among 9 -12 year-olds. In a study of 800 mothers, only 27% said their children play outside every day. Did you play outside when you were growing up? Are your children outside as much as you were? Be honest with yourself!

Interestingly enough, rural mothers and urban mothers both report less outside play, and it is the same in other developed nations.

Other research indicates that not only do children play outside less, they are more and more restrained in both indoor and outdoor environments.

Think about high chairs, baby seats and car seats, even the little carriages children ride in as their parents jog. They are not moving.

As a mother and as a Montessori teacher, I have always valued what Montessori taught us – that movement is the law of the child’s being. One research study published in an English medical journal documented that nearly 80 three-year-olds were averaging 20 minutes of activity per day. That really stunned me. In my experience, if you provide a free environment, children are moving pretty much all day long.

There is a lovely section of Louv’s book where he quotes from Bill McKibben about the endless exploration possible on one’s own home turf. He describes a mountain near his home. “The mountain says you live in a particular place. Though it’s a small area…it took me many trips to even start to learn its secrets. Here there are blueberries, and here there are bigger blueberries.”

Know Your Locale

Know Your Locale

Great vacations to fabulous places are wonderful, but exploring your own space is not so bad either. A middle school teacher from the Santa Cruz, California Bay area, tells in Louv’s book of her annual class trips to the high Sierras.

She made the assumption that the children knew their immediate area and these trips to the mountains would be of more value. While they loved the trips, she soon discovered that the children did not know their own locale and in fact felt disconnected from it. Her classes began exploring the wonders of Monterrey Bay and local forests only to find that 90% of her students had not been there.

I had a similar experience with upper elementary children. We live in Bozeman, Montana, near Yellowstone National Park and I assumed that all of the children had been there. But I found that most had not. So for several years in a row, in addition to our daily hour of outdoor play, we planned some fundraising and made overnight trips to Yellowstone.

As an old Indian saying goes, “It’s better to know one mountain than to climb many.” Perhaps we can learn from this to get ourselves more connected to nature, and make sure our children get connected and stay connected.

As an old Indian saying goes, “It’s better to know one mountain than to climb many.” Perhaps we can learn from this to get ourselves more connected to nature, and make sure our children get connected and stay connected.

Making Connections

We can garden, we can hike, and we can simply take nature walks. The best kind of nature walk is guided by the children and what catches their attention. They may not care one bit about a great view, but they care passionately about the bugs they find under a log. They may not care so much about the beautiful flowers as the smell of different plants. Let them be your teacher about what interests them and be prepared to give yourself to that pursuit.

Children especially love to harvest. Obviously we have to plant first, but if we plant things that come to fruition quickly, it may be a good way to begin. Help children expand their natural care for living things by watering and tending plants; setting up bird feeders, aquariums and terrariums; and helping to care for pets.

One key idea to keep in mind is to share what you love to do outside and observe your children so you can better understand the activities that make them calm and happy. Nurturing our connection with nature helps us become more integrated people and this, rather than alienation from nature, is the legacy we would pass on to our children.